Not getting lost in process

Debates about political process and endless delays in making decisions threaten to weaken trust in our democratic institutions especially with regard to pressing matters like the provision of adult social care. Politics has become a “prisoner of process” (Bagehot, 2025).

Bagehot makes a good point and cites Blair in support of the observation that process, rather than being the means to the end, has become an end in itself. Bagehot draws on Stafford Beer’s (not attributed) POSIWID heuristic – the purpose of a system is what it does – to suggest that the system’s purpose has become an endless cycle of debate without action, although, in passing, observing that deliberation is necessary to “ensure that decisions are simply not made” (my emphasis). This is all good, but I think there are a number of conceptual errors that unhelpfully muddy the argument.

Starting with Beer’s POSIWID, it is a simple observation that system is being interpreted here in a narrow sense. We would hope that any system of governance has feedback mechanisms in it. Rather than a simple linear sequence of steps we would expect something like deliberation → action → observation (of effects of actions) → comparison → deliberation → …, where the comparison step derives an error signal based on the difference between what was intended and what happened. This system should operate in a continual cycle of feedback – it is both unlikely that our actions achieve the desired effect and the world keeps changing anyway. While we might conclude that the evident purpose of the system is to endlessly deliberate i.e., deliberation → deliberation → …, we could go a bit further and observe where the system is broken – the action element is missing and therefore the feedback loop is not operating. I think we would both agree that the system needs to be repaired.

POSIWID is useful and the elicitation of feedback loops, at any desirable level of detail, provides a powerful analytical tool; but I believe there is another way of looking at this problem and the use of a process approach offers some benefits, rather than being consigned in the narrow sense to a trap of deliberation. The key can be found in the way in which we use language in our analyses. I have previously railed against the use of language like ‘solution’ and ‘fix’ in the context of complex problems, but in the analysis of the feedback loop above I rather consciously used ‘deliberation’, ‘action’ and ‘observation’ to emphasise the linearisation of what should be a system and that this arises from the nominalization of elements that should be thought of as verbs.

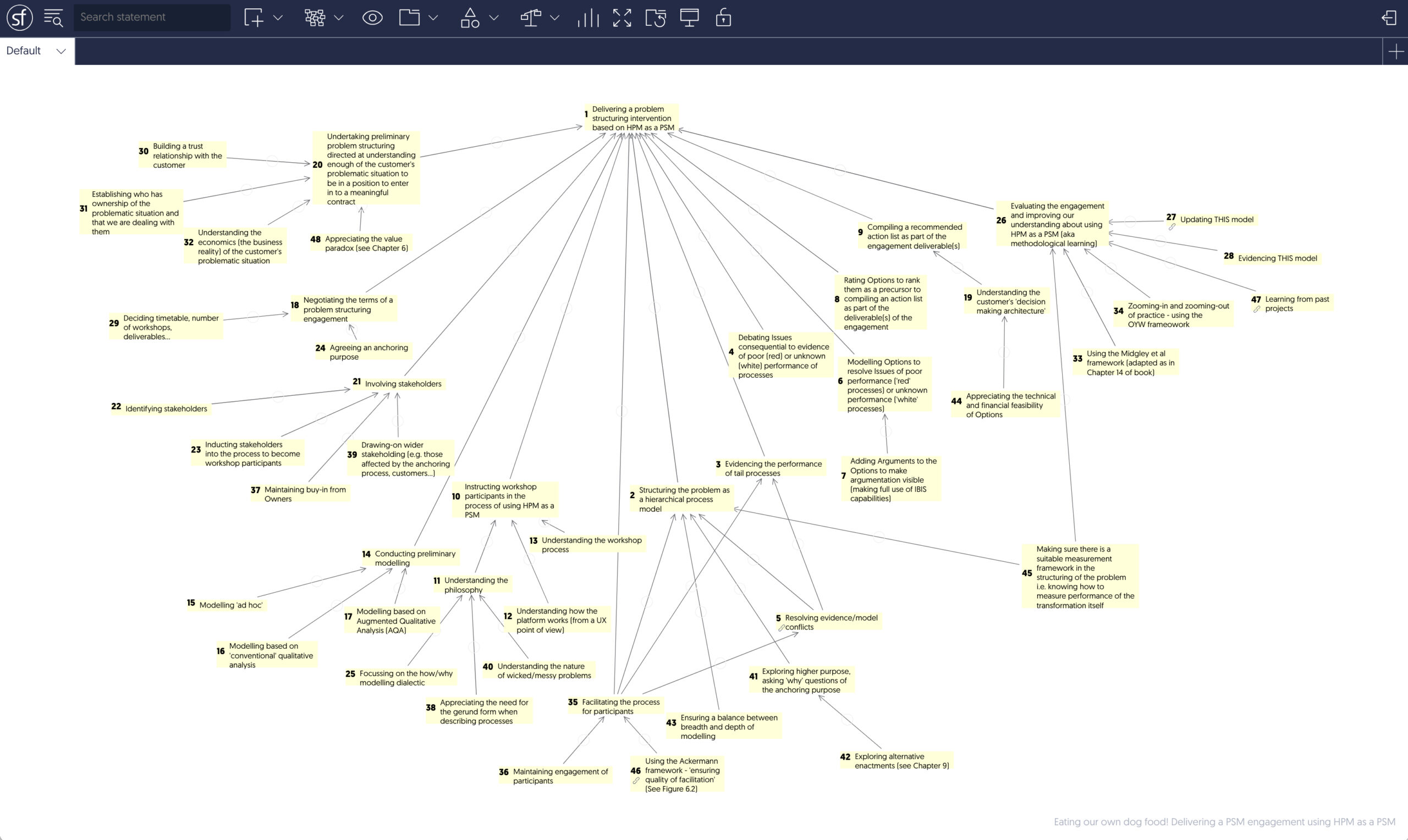

Getting stuck in a process of deliberation, or an endless sequence of deliberations, is likely when all the actors, including analysts and commentators (expert and otherwise), are constrained by their nominalizations. A better conceptualising of process thinking is to think of governing as a process and that for it to perform it must consist of further processes such as deliberating, acting (or effecting change, or intervening) and observing (or measuring). These processes are all necessary for governing but none are sufficient, by themselves, for properly enacting the process of governing. Note the use of the gerund form of the verb to convey a sense of continual ongoingness of the process. We can decompose this schema (or model) to any level of detail that is required using conditions of necessity and sufficiency as a test on whether a process is required in the model.

Coming back to Bagehot’s analysis, we can clearly agree that the process of acting is not working well, but it cannot be reduced to a simple intervention that is yet to happen and that will somehow ‘fix’ the problem. The process of deliberating is obviously not working well either, it is clearly not sufficient by itself to enable the process of governing and our measure of its performance should of necessity include its commissioning of useful planning to enable acting. Rather than being prisoners of process, we would be better served by realising that processes are all there are, both in the world and in our ways of intervening in the world. To do this, amongst other things, requires a change in our language, away from nominalizations, especially ones like ‘action’ and ‘solution’, and recognise that acting or intervening is a continuing and ongoing process and may be enacted at any level of scale (socially, temporally, spatially,…).

In the case of adult social care there is clearly a whole lot of process detail that is completely missing between deliberating and intervening and nobody seems to be talking about it. We are left with unedifying analyses and useless solutionist traps.

- Bagehot. (2025). How means conquered ends: British politics has become a prisoner of process. The Economist. Retrieved 9th January 2025, from https://www.economist.com/britain/2025/01/08/how-means-conquered-ends